We Went Up to the Mountains: The Return of Displaced Girls in Sinjar

Published: Nov 28, 2022 Reading time: 4 minutes Share: Share an articleIt’s Monday afternoon and the school bell announces the end of another lesson. The girls funnel out of their classrooms and fill the hallways. The patter of black shoes and children’s laughter rings around the corridors and out towards the playground. This could be any school in any town; but these girls, many of them Yazidi, have been displaced at least once.

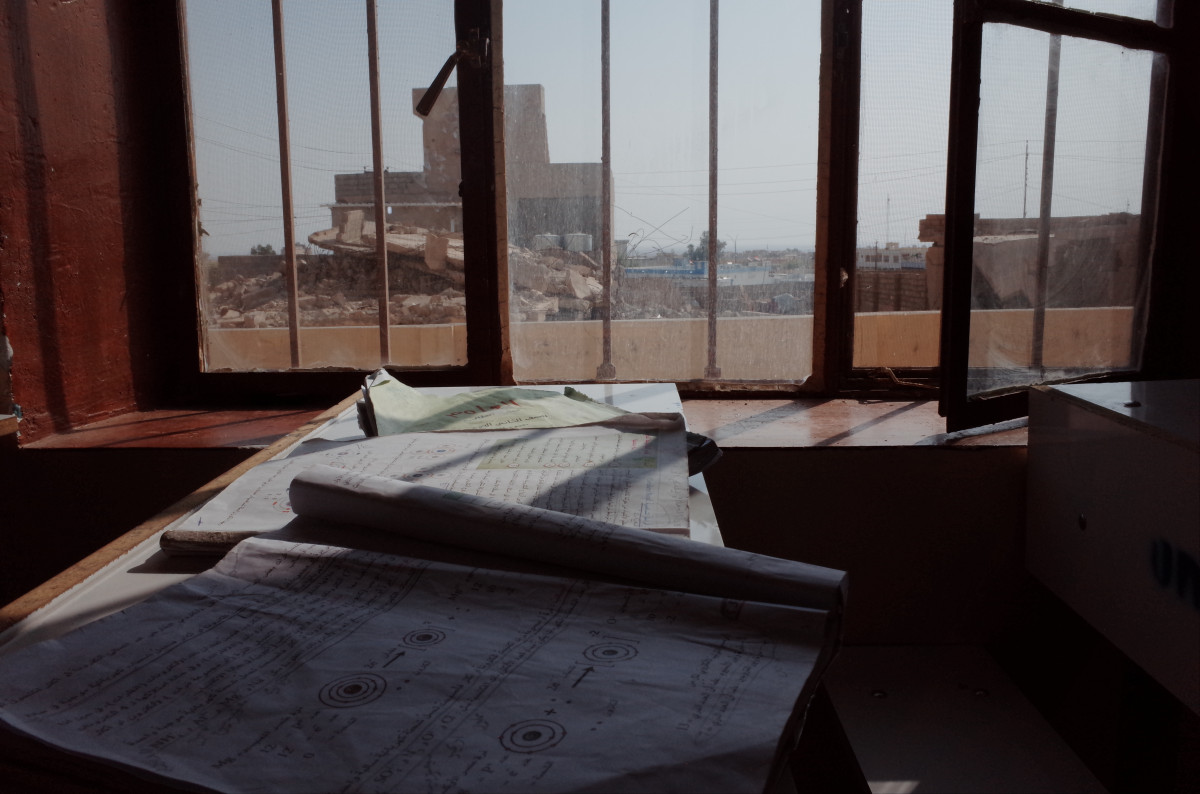

From the classroom windows and beyond the playground walls, the land slopes into the foothills and ruins of Sinjar’s old town, and beyond that, the mountains themselves. These shrub-covered peaks that overlook Sinjar Secondary School for Girls are a reminder of the suffering so many children and families endured. When the so-called ‘Islamic State’ entered Sinjar under cover of morning darkness on August 3rd, 2014, 50,000 Yazidis fled to the mountain range.

“We were preparing to go to the hospital when they said that [ISIL*] was approaching Sinjar,” says Elias, a local nurse and father of one of the students. “We went up to the mountains and stayed there for four days without food or water, with [ISIL*] following our every step. My family and I barely kept ourselves alive. We saw lots of people die of thirst right in front of us.”

Many of the students were young children at the time, some were too young to remember anything at all. But between the blurry half-memories, some scenes remain etched in their minds. Fatima was only seven years old when she was forced to flee Sinjar with her family.

“We were really hurt by [ISIL*]. I was very little and don’t remember much. While we were on the road out of Sinjar, they stopped my cousin and her husband. They beat him to death. She couldn’t take it and attacked them, so they killed her too. This happened in front of my eyes.”

Fatima is an otherwise ordinary teenage girl. She attends school 5 days a week, spends time with her friends, and goes for picnics with her family on the weekends. She sits in the principal’s office, minding not to wrinkle her uniform as she waits for her older sister to pick her up after class. “I really enjoy going to school here with my friends,” Fatima says, “I enjoy our Arabic lessons – I want to be a lawyer one day.”

Fatima and her family returned to Sinjar two years ago. The school she now attends is supported by PIN with funding from the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA). With this funding, PIN provides remedial classes, student kits, training for teachers and facilitators, and psychosocial support for children, among other activities. In doing so, PIN’s MFA-funded project supports local schools in providing much-needed education for returnees.

Re-establishing education in Sinjar has enabled children like Fatima to have a second chance at a normal childhood. There are 850 students here, and almost all of them have endured displacement, conflict, and tragedy. So too have the teachers, including the principal, Huda.

“Before 2014, Sinjar was a city of peace and we were all living together; Muslims, Christians, and Yazidis,” she says. She is one of Sinjar’s minority Muslim population. But in the face of the so-called ‘Islamic State’, Muslims too experienced the same hardships as their Yazidi neighbours.

“They started killing, shooting, and destroying many churches and places so people were forced to run to the mountains, but [ISIL*] followed us and captured many people. We spent the nights travelling by foot just to survive. I took shelter in a barn for three days to hide from them.”

When she returned to Sinjar and became principal, Huda found that as a Muslim, some of her students were now afraid of her. “In the beginning, it was hard on them because I am a Muslim teacher and most of them are Yazidi. But when the students saw how I treated them and how I took care of them they started to accept me, especially when I explained that I knew their suffering since we had been through the same hard times,” she said,

The people of Sinjar shared a tragic period of their history. But now, they are rebuilding their future together: education is a vital component of the long-term reconstruction of the town’s community.

The bustling noise from the corridors begins to fade, and the sun starts to sink, sending long shadows out across the playground. A silence sets in from the mountains and across the town. The children have gone home, and Huda walks between the empty classrooms. “I do my best to be present in their good and bad times,” she says softly, “it’s because I really love them.”

*so-called ‘Islamic State’

Thank you to the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs for helping to fund PIN’s education activities in Iraq. This support is crucial to enable PIN to continue delivering vital support for vulnerable communities.